![[MetroActive Movies]](/movies-arts-entertainment/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | SF Metropolitan | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Modern Gothic

Lynn Hershman Leeson's 'Conceiving Ada'

By Michelle Goldberg

Tillie, the old-fashioned porcelain doll perched in a cabinet in Lynn Hershman Leeson's 10th Street studio, abruptly turns her head, seemingly of her own accord. There are cameras hidden in her black eyes that feed a monitor next to her, and when Tillie looks at your face, your startled expression fills the screen.

All the pictures from the screen are constantly uploaded online, so that millions are free to scrutinize your unguarded image. Through a sophisticated use of telerobotics, viewers on the Internet can control Tillie's movements, clicking to direct her gaze around the room.

Like a bastard child of Mary Shelley and George Orwell, Tillie is a surveillance system in a pretty Victorian package. Technologically advanced, frighteningly gothic and fraught with dystopian implications, she typifies Leeson's work, which almost always combines an explicitly feminist stance with a groundbreaking use of computers.

Leeson has been fairly famous in art and technology circles for years, but now, with a midcareer move to feature film, she's primed to captivate a much wider audience. Her debut feature, Conceiving Ada (starring art-house ice-queen Tilda Swinton, Francesca Faridany, Karen Black and Timothy Leary), crisscrosses between centuries to tell the interwoven stories of Emmy, a San Francisco virtual-reality researcher, and Ada Lovelace, the historical figure who obsesses her. The daughter of Lord Byron, Lovelace created what is now considered to be the first computer language, defying the strictures of her Victorian age to indulge her passion for mathematics (and for extramarital affairs). In the film, she becomes a symbol both for fierce female genius and for the special relationship that Leeson sees between women and machines.

"Women have traditionally been closed out of everything except when it's really new and nobody sees a commercial prospect for it," Leeson says. "So women have kind of ventured into things that are available. Now that's happening on the Internet with a lot of lists and websites and chat forums. In the '70s and '80s, it was happening with video. As these things were then appropriated by patriarchal companies, women were closed out of any kind of commercial or executive positions."

Leeson should know--she's been on the cusp of most of her generation's technological innovations. In fact, she divides her work into two categories: BC, or "Before Computers," and AD, or "After Digital." In 1979, she created the first interactive videodisk--a precursor to CD-ROMs. The disk, titled Lorna, allowed viewers to influence the fate of an agoraphobic, house-bound woman whose terror of the outside world was exacerbated by the TV news.

Through a remote control unit that resembled Lorna's own TV changer, the audience could access objects in Lorna's apartment or eavesdrop on her phone conversations, all in the interest of guiding her toward freedom. There were three possible outcomes--Lorna shoots her television set, commits suicide or ("What we Northern Californians consider worst of all," as Leeson says) moves to L.A.

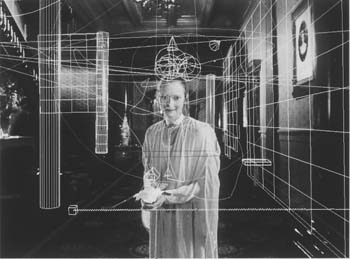

Leeson was equally innovative in making Conceiving Ada. An ultra-low-budget period piece sounds like a contradiction in terms, but Leeson pulled it off by digitizing and manipulating still photographs taken in Bay Area Victorian inns and then using them as the film's "sets." Actors performed against blue screens, and the whole movie was shot in six days, with backgrounds added during production. The result is remarkably authentic--in fact, James Cameron used a similar process in Titanic, which was made after Ada.

The process of filming Conceiving Ada.

"I got funding for this film, and then I realized I had to figure out a way to do it," Leeson explains. "Basically, I didn't know how to do anything, but I have a kind of intimacy with technology because I've been working with it for 20 years, and it just seemed to me that this ought to work. We didn't test it or anything--we just did it. It never occurred to me that nobody had done it before. It just makes sense."

But as is the case with many science-fiction writers, Leeson's fascination with technology is tempered by an intense uneasiness about its destructive potential. Frail, pale Swinton portrays Lovelace as a woman whose body is too weak to contain the force of her brilliance and her libido. She's driven to near hysteria and early death by the patronizing indifference and oppression of her male collaborators and her obtuse, pious mother.

Similarly, Emmy is nearly undone by her obsession with resurrecting Ada through virtual reality. Technology in Leeson's other work is similarly menacing--throughout her studio are photographs of women whose heads have been replaced by monitors or video cameras. In her "Digital Venus" series, old-master nudes are overlaid with pictures of wires and circuit boards that seem like veins, as if one were looking through the skin of a cyborg.

The dangerous interplay among technology, voyeurism and violence is illustrated most pointedly by Leeson's America's Finest, a work based on an 1888 gun that substituted film for bullets. America's Finest is an M-16 rifle with an interactive video inside its sight. Pictures of war confront the viewer, and the only way to change the scene is to aim and pull the trigger, which, depending on what you shoot, starts another series of images.

"A lot of this is based on questions about how technology affects our ethics, our morals, our sense of ourselves, our identity," Leeson says. "I think that technology does make you fearful, it does make you have strange images of yourself." And all this is only intensified for women, Leeson says. "I think women are targeted. From Edison's first work, which was a peepshow of women dancing, women have been the object of what people looked at and distorted--and our whole sense of perception is therefore distorted. Women more than men have been the voiceless victims of voyeurism."

That will only change, Leeson says, when more women artists and directors create work and find audiences. "I was talking to Ruby Rich and reading her book Chick Flicks, and it doesn't look real hopeful for the women who are able to actually get work done to get it distributed in a major way. Usually it takes women seven years to make their second film, versus two years for men," Leeson says.

Fortunately, we should be seeing Leeson's next film much sooner. She recently won a coveted Sundance Fellowship, in which the Sundance Institute helps up-and-coming filmmakers fine-tune their screenplays and get their movies produced. Swinton has already agreed to appear in the new film, and Leeson is hoping to cast Johnny Depp and David Bowie as well.

She's already written the script, and from her synopsis, it seems like the quintessence of the work she's been doing for decades--it's Bride of Frankenstein told from the bride's point of view. "It's about the consequences of what we're doing at this point in time with cloning, while staying true to that first story of artificial life," Leeson says. A French company has already volunteered to do all the post-production for free, and Leeson expects to have much more advanced computer animation and imagery than she did in Ada. Conflating anxieties about out-of-control science and about reproduction, Leeson's critique promises to do for the silicon age what Shelley's did for the electric era, and no one seems better suited than she is to bring such visionary ideas to life.

[ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc.

![]()

Digital Venus: Tilda Swinton in 'Conceiving Ada'![[line]](/metropolitan/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/metropolitan/gifs/line.gif)

Conceiving Ada shows Feb. 19-25 at Lumiere Theater, 1572 California St., 415/885-3200. To visit Tillie, go to www.lynnhershman.com.

From the February 1, 1999 issue of the Metropolitan.