![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | SF Metropolitan | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Art Damage

The Billboard Liberation Front commemorates two decades of advertising improvement

By Michelle Goldberg

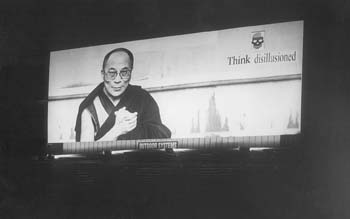

If you've lived in San Francisco for a while, you've probably been surprised and delighted by the work of the Billboard Liberation Front. Maybe last summer you looked up at an Apple billboard and did a double take when, instead of the trademark "Think Different," you read "Think Doomed" or "Think Disillusioned." Or perhaps last fall it took you a moment to realize that Levi's wasn't really using Charles Manson to sell jeans, or, in '95, that the man in the 24-Hour Nautilus ad didn't originally have his dick out.

It's been 22 years since the Billboard Liberation Front began its guerrilla war on the boredom and banality engendered by the corporate annexation of public space. Working in the wee hours, the renegade pranksters scale billboards all over the city and slyly alter them. Now those who have missed their most exciting work can get a glimpse of the group's subversive oeuvre at their first-ever gallery show, "The Art of Midnight Editing: Two Decades of Culture Jamming and Drive-by Advertising Improvement," through April 1 at the Lab. The show brings together the BLF and their contemporaries, including Mark Pauline of Survival Research Laboratories, anti-ad artist Ron English, filmmaker Craig Baldwin and those masters of parodic musical pastiche Negativland (performing April 1 as Positiveland).

Jack Napier, the pseudonymous spokesman for the BLF, founded the group in 1977 with Irving Glikk after the two discovered the joys of billboard improvement with the San Francisco Suicide Club (a stunt that resulted in Napier's only billboard-related arrest). A bearded, elegant man in a suit and stylish trench coat, he looks more like a classics professor and seems, like the group itself, more the winking provocateur than the fire-breathing radical.

Metropolitan: In your manifesto, you write, "Spiritualism, literature and the physical arts: painting, sculpture, music and dance are by and large produced, packaged and consumed in the same fashion as a new car." Is the eradication of the lines between high art and pop culture necessarily a bad thing?

Jack Napier: I'm not going to place a value judgment on it. I think it's inescapable that it's happened. I take it you're not questioning that. That's a funny thing, because 15 years ago that would have been a huge argument. Now it's a given. If you were a little bit older, it would have been an extreme issue. To me it's not anymore. I give up. It's obvious that that's already happened. It's pretty dispiriting in certain respects, but I'm not really sure what's going to happen next.

Metropolitan: At least in universities, lots of leftists and radicals celebrate the end of that distinction as being democratic and populist.

Jack Napier: Why should art be democratic? As I said, I'm kind of holding my opinion in reserve until I see where things are going to go. I think we're in a transition period right now with popular culture kind of consuming everything. The center of the universe in our world now seems to be Madison Ave and Hollywood, and everything emanates out of there and ricochets all over the place. That's what people are interested in, that's what motivates them, that's what they aspire to. If you look at it one way, it can be very disturbing and frightening. I have a lot of interests besides billboards, and my interests in literature and art would probably be considered elitist.

Metropolitan: But your work is in the most democratic medium imaginable, and it's so rooted in advertising and pop culture.

Jack Napier: I don't think politics necessarily has a place in art, and I don't consider what we do to be art. At all, actually. It's funny that anybody would think that it was.

Metropolitan: Is your work a kind of protest, then?

Jack Napier: I don't know. I don't think so. Advertising is becoming the common language to such an extreme degree, how can you protest it? It's just like protesting air, isn't it?

Metropolitan: What keeps you going if it's not art and it's not politics?

Jack Napier: It's a lot of fun, mostly. It's exciting, it's adventurous. It's fun to communicate with a large group of people. I've sat and watched people go down the street and look at billboards that we've done--and that's one of the reasons I don't like to do things that would be considered too offensive, because I'm not interested in upsetting people. I don't want to do anything that makes anybody's potentially grim, horrid existence any more grim or more horrid. I'd rather do something that would lighten their day a little bit.

Metropolitan: Does it bother you that advertising itself has gotten so anti-advertising that it's hard to satirize? Something like the Charlie Manson billboard, I don't know if I would know right away that that was a parody anymore. And, as the Bay Guardian article on your site says, there was that Plymouth Neon campaign that was supposed to look as if the billboard had been vandalized to say "Hip" or "Chill."

Jack Napier: In another five years they'll probably be using Charlie Manson to sell stuff. So yeah, we do have to run pretty fast to keep ahead of them. I know some of the advertising agencies are already keeping an eye on the billboard hackers to see what they can use to sell their product. The first time I ran across it I found it annoying, and then I thought I can either be pissed off about this or I can do something about it. It was the Plymouth Neon campaign in '94, and my girlfriend and I were driving around and she said, 'Look, someone did a billboard over here.' So we stopped to look, and it took me about a minute to realize, wait a second, that wasn't a tagger. I was really pissed, and then I thought about it for a while and I started laughing. I knew that the ad executives who came up with that over two or three martinis would be very well paid and that the campaign would be successful, which it was. The Plymouth Neon sold like hotcakes.

Metropolitan: Have any of you ever considered going into advertising since you understand it so well?

Jack Napier: Our minister of propaganda is vice president of an advertising agency. I've worked in and out of graphics and advertising-related fields for over 20 years. Three other people involved work in advertising or some closely related fields. I have one friend who used to do all of our graphics who's a VP for an Internet advertising concern and another one who works for one of his competitors. Maybe for some of my associates [the BLF] is a way for them to expiate any guilt that they might feel, I don't know. Advertising is the language of the culture now. There's no way to fight it.

Metropolitan: Did you feel that way when you started the BLF at 19?

Jack Napier: No, frankly I just wanted to climb things and swing around on ropes. Part of it was the idea of putting my own message up; that was attractive, but it was largely the clandestine nature of the activity. Another thing I like to promote is the idea that people can do this kind of thing because it makes them more alive. You're really in the moment when you're doing something like this--you pretty much have to concentrate on what you're doing or else you'll kill yourself or be arrested. It's not for everybody, but the concept of changing any advertising image that comes to you, just editing it yourself in your own mind, that is for everybody. I have no illusions about my group having that much influence over anything at all. However, people always find some way to subvert the powers that collectively oversee them. That's my big hope for humanity. It's pretty small, but there's some hope. Maybe.

[ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc.

![]()

Kapital Crimes: BLF fights back against corporate doublespeak.

"The Art of Midnight Editing" runs thru Apr 1 at The Lab, 2948 16th St. For more information, call 415/864-8855 or go to www.billboardliberation.com.

From the March 15, 1999 issue of the Metropolitan.