The Havana Desk

Che Stadium

By Dan Pulcrano

We roll into Santa Clara, Cuba, at 4:30am, after an all-night drive across Eastern Cuba, dodging horse carts, bicycles, Russian trucks, stray dogs and cows; smoking cigars and drinking guayabita, a dry tropical fruit brandy from the end of the island where the world's best rolling leaves are grown and aged. By 6am, the streets of Santa Clara are filled with people, and shaved-ice vendors set up their concessions. We reach the fenced-off area beneath Santa Clara's massive Che memorial before 7am. Though we're two hours early, people are already pushing and shoving, like in the front rows of a rock show.

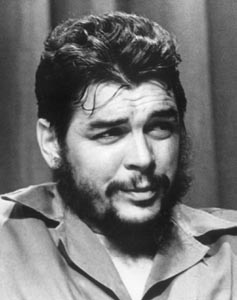

We are here to watch the funeral of Che Guevara, the great revolutionary who helped the Castro brothers, Fidel and Raul, win a three-year guerrilla war to overthrow a kleptocracy notable for turning Havana into a Mafia-operated casino.

And while Che had been a wine-drinking romantic in his youth, debauchery had no place in the early days of an idealistic revolution. Havana's roulette wheels stopped spinning in 1959. Che ran the Finance Ministry (early peso notes bear his signature) and later became minister of industry, where he spent days lifting sacks of sugar and coffee in displays of radical egalitarianism. As with entrepreneurs who tire of managerial details when the company grows big, signing bank notes and cutting factory ribbons grew old fast. He left to pursue other ventures. His golden parachute was Fidel's promise to back his peasant rebellion in Bolivia, but CIA-directed Bolivians captured and killed him, cut his hands off and stole his wristwatch as a souvenir.

Che became subsequently became an international pop icon, decorating college dorm rooms and Rage Against the Machine CDs. A couple of years ago, Swatch issued a watch with Che's picture under the crystal. I sent one of these to Fidel in 1995 through an intermediary. Fidel, if you are reading this, no thank-you note is necessary, but an autographed picture would be great.

Anyway, Che's bones were found earlier this year in an unmarked grave alongside a dirt airport frontage road in Vallegrande, Bolivia. This was fortuitous timing for the Cuban government, which had been planning to commemorate the 30th anniversary of his death; there is nothing like a memorial ceremony with real bones.

By 8:30am the chairs on the viewing stand are half-full, the sun is hot and a drumbeat thunders from the sound system. A large empty area for marching soldiers and military bands separates the crowd from the dignitaries' bleachers. Right about 9am, the crowd breaks into spontaneous applause, and I notice a tall figure in green fatigues near the podium. It's Fidel Castro! He clasps his hands together and stands erect as guitar music kicks in.

The arena-sized crowd sings along to the familiar song about Comandante Che Guevara and the battle of Santa Clara, as arms and flags wave slowly overhead and tears stream down cheeks. Che's tiny, flag-draped casket rests atop a flower-strewn jeep trailer between the crowd and the reviewing stand. A schoolgirl in a berry-colored skirt and white blouse screams out over the PA system: "My friend, my companion, my model, my light, my star." Silvio Rodriguez performs a song on his guitar.

(San Franciscans who danced to Celia Cruz at the Bill Graham Civic last month might be interested in knowing that that the anti-Castro salsera skipped a festival in Puerto Rico this summer rather than apologize to Puerto Rican salsa star Andy Montanez, whom she took to task for hugging Rodriguez.)

After the proper warm-up, Castro advances toward the podium, and the crowd chants "Fidel! Fidel!" followed by rapidly accelerating clapping. Anti-Communist Cuban-Americans in Miami claim that Fidel pays people to cheer. No one offered me a check, though.

Fidel starts his 16-minute speech (mercifully, it was too hot for a seven-hour one) in a tentative voice that turns stronger as the oratory slides into its cadence and groove. Punching the air with his forefinger, he takes imperialistas and oportunistas to task for a wide range of global problems and vows, "We will keep fighting for a better world." A woman faints from the heat and knocks down one of the barricades. A 21-gun salute follows.

Che's restless spirit is put to rest at the base of the monument with full military honors, and Fidel embraces the guerrilla fighter's surviving relatives. I wonder how Che would have felt about the formal ceremony. His Kerouac-like diary of youthful motorcycle jaunts around the South American continent enthused about his "resolutely bohemian ways," and "new horizons, free from the shackles of 'civilization'."

That night, we make record time on the unlit highway by tailing one of the fast-moving utility vehicles of Raul Castro's security agency back to Havana.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc.

Che Guevara

Editor's Note: The Havana Desk is a monthly report from The Metropolitan's Havana bureau to keep readers in touch with the only country in the hemisphere that Americans are not allowed to travel to, or buy cigars from.

From the November 1997 issue of the Metropolitan.

![[MetroActive Features]](/metropolitan/gifs/feat468.gif)