![[MetroActive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | SF Metropolitan | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Hide and SECA

SFMOMA seeks out local artists for a hit of exposure with SECA Art Award

By Apollinaire Scherr

Every couple of years, the head curators of painting and sculpture at SFMOMA and a gaggle of collectors, dealers, students and artists from the museum's Society for the Encouragement of Contemporary Art (SECA) pile into buses and drive to the studios of 30-odd Bay Area artists, selected from hundreds of slides.

After conversations with the SECA volunteers, the museum narrows the list of artists down to seven, and the curators, without gaggle and buses, return to the studios. A few months later, three or four artists are announced as winners of the prestigious SECA Art Award. Besides providing sudden clout for people who have been doing solid and steady work for several years, the award also includes a four-month show at SFMOMA. (This year's edition runs Jan. 22 to April 6.)

It's the art work--what SFMOMA's Janet Bishop calls "its strength of individual conviction"--that wins the award. But Gay Outlaw, Rigo 99, Chris Finley and Laurie Reid could also have won awards for charm and unpretentious thoughtfulness.

Does the SECA award change artists' lives?

Candy-Colored Dream

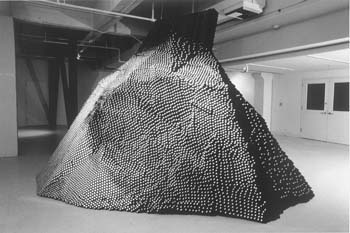

Out here in the wild west, "Gay Outlaw" sounds like a literal-minded drag queen, not the given name of a 38-year-old married woman. But as a sculptor who animates her forms with unlikely materials--garden hoses, rubber, pencils, chalk, caramel--Outlaw displays a good deal of native adventurousness and eccentricity.

"I try to start from an intuitive place. Do I have an inexplicable urge to glue chalk together? What would that mean, to glue chalk together?" the Alabama native explains, parodying her odd obsessions.

Her large Hunters Point studio is crammed with crates of materials and scary-looking industrial equipment for making casts and molds. On a nearby table, translucent brown figures--Mountain, Cathedral and Dinghy--are beginning to melt. (A tiny puddle of former sculpture sticks to my shoe.) As a one-time pastry chef for the Silver Palette restaurant in New York, Outlaw has a taste for caramel. But why pencils and hoses?

Near the caramel test runs for the SECA show lies a beautiful rubber tree limb that expresses all the suspended motion of a natural branch. Constructing large solid forms (cones, mounds, mountains, branches) out of small cylinders (pencils, chalk, hoses or negative molds made from these objects), Outlaw alternately cuts against the smaller cylinders' grain and leaves their surfaces smooth, a process that instills them with tension, with life.

Coming late to art, after her pastry chef career and a brief foray in accounting (which she calls "the more conservative route to life"), Outlaw is honored to receive a SECA award. She plans to continue as she has, "making work, and having the opportunities come when they come, in their time." She's doesn't mind that faced with her caramel sculptures, collectors are still fly-shy.

This Space for 'Huh?'

The wall behind the shell gas station at Fifth and Folsom is emblazoned with the word "EXTINCT" above yellow and black warning lines. The sign is an anti-advertisement. Instead of glamorizing winners by fetishizing their logos, it memorializes the world's biggest losers--the irretrievably lost--by omitting their discarded names.

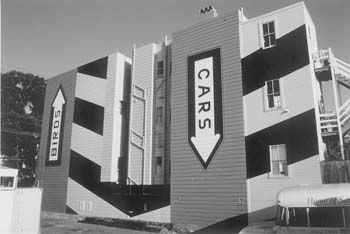

This and many other public murals in San Francisco are the work of Rigo 94, Rigo 95, 96, 97 or 98. One late November afternoon in his Outer Mission loft/converted carport, I ask Rigo 98 if it isn't a bit dehumanizing to go by a number--and a different one each year, at that. He answers, in his thoughtfully European fashion, "Yes, definitely. It's kind of like inoculating yourself with poisons to develop antibodies. I think that as artists, what we do ends up describing the times that we're in. So instead of being an individual connected to my family history and a place, every year is a new model." (But to appease me, he explains he's from an island off Portugal and is the son of postal workers. He's lived in San Francisco for 13 years now, since he was 19, and misses home and his mother. "She feels like a lost bird to me, and I to her," he says, very quietly.)

For the SECA show, this year's model has created a mural, on an abandoned building near SFMOMA, of giant twin arrows directing us to "SKY" and "GROUND." Inside the museum, an enormous landscape drawing titled Looking at 1998 San Francisco From the Top of 1925 surveys the city, as seen from the roof of a 1925 skyscraper on Montgomery Street. "In the time it takes me to draw the landscape, it's already changed by 10 floors," Rigo says, pointing to a building in the drawing that's under construction. "And Sky/Ground will get covered over." A high-rise will soon take the place of the building it's painted on. "A museum can preserve and protect only a certain type of art from disappearing. But the art it protects is isolated from its context: the landscape drawing grows more and more obsolete."

In the Game Room

After attending art school in L.A., Chris Finley returned to his hometown of Petaluma, where he paints in an old chicken barn for eight hours a day, stopping when the fumes get to him. In the evening, he watches TV with his former high school sweetheart now wife--and whittles.

The after-hours TV is as important to Finley's art as his day job. "I look at the mainstream of what is going on--the Internet, the way www.com is on every single commercial now--and get keys to how people look at things," he says. Finley creates multipart installations as buzzy and giddy-making as a Green Day video or the Mario Brothers games his latest works refer to.

Level One had viewers jumping on a trampoline to catch sight of a painting hidden behind a wall. The series of paintings in Level Two work together like nested computer files or (for the Luddites among us) like a pop-up book, each painting expanding the image of the previous work. Level Three, made for the SECA show, is a full-on obstacle course.

Subtitled Buzz No Thank You MMM Pizza With Steamy Crotch Hippitty Hop Head-Butt Moo, the piece leads viewers through a corridor ("kind of like in Raiders of the Lost Ark or a car wash"), where air fresheners and noise boxes surgically removed from stuffed animals hang from baskets, to a hyperactive portrait of two women sunk deep in a monstrous olive pizza. Head butt the hippitty hop that's suspended over a steam vaporizer and in front of the women and--voilá!--the painting moos.

"I'm not really trying for some meaning or afterthought, but more a different way of experiencing art--a fun, weird, crazy experience," Finley explains. "When you're done with it, then fine, you're done with it. It's still going to be in your head."

Water Damage

Mapping the elemental process of water settling into, shrinking and swelling paper, Laurie Reid's watercolors are more water than color. A thin alluvial ridge threads its way across the pure, enormous expanse of rag paper in one piece; another gives an impression of wafting white brick wall. More than the slightly gray tint Reid gives the water, it's the light reflecting off the swollen and cracked paper that fills her work with evanescent beauty.

Reid, who, at 33, has an easy whimsy that complements her paintings, came to this richly tactile minimalism almost by accident. Before grad school, she took a hodgepodge of community center art classes, including a dabbler's course in traditional watercolor.

"They'd say, 'Today we're going to paint a wicker basket' or 'Today we're going to do a fisherman and waiter scene.' I loved it," Reid says, "not necessarily the subject matter, but the paint." But when she decided to apply to California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, she didn't have much to show. " 'I know this doesn't look right exactly,' I told them, 'but I really want to do [art].' And they went for it."

On the first day of school, the dean gave the incoming students the usual hortatory speech about wasting no time, getting right to work, yadda yadda yadda. Having just arrived in town, her supplies packed away, Reid took him seriously, showing up at her studio with what she had on hand: a kiddie watercolor kit and a pad of paper. "I kept thinking, 'Well, I'll exhaust this and get back to whatever,' and I never did. I never did. The more I get into what actually happens--the way paint settles in the paper--the more it keeps opening up on itself."

[ San Francisco | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc.

![]()

Gay Outlaw's Black Hose Mountain, 1998.![[line]](/metropolitan/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/metropolitan/gifs/line.gif)

Rigo 97's Birds and Cars, 1997.

Chris Finley's New Age Dom Deloise with Hikers and Smashed Yellowjackets, 1997.

Laurie Reid's Mouthful of Rain (detail), 1996.

From the December 21, 1998 issue of the Metropolitan.